Abstract

RNA transfection methods are essential tools for studying gene function and developing RNA-based therapeutics, including vaccines and immunotherapies. Delivering RNA efficiently into immune cells such as T cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells remains challenging due to cellular defense mechanisms and RNA instability. This review compares four major RNA transfection approaches—viral vectors, lipofection, electroporation, and RNA-loaded lipid nanoparticles (RNA-LNPs)—in terms of efficiency, cytotoxicity, and suitability for immune cells. Viral transduction achieves high efficiency but poses safety concerns, lipofection is simple yet less effective for some cells, and electroporation enables delivery to hard-to-transfect cells at the cost of viability and no in-vivo capabilities. RNA-LNPs stand out for RNA protection, tunable delivery, and clinical potential. Emerging hybrid strategies may further improve safety, targeting, and efficiency in immune cell engineering and RNA-based therapies.

Introduction

RNA transfection has become a vital tool for studying gene expression and regulating immune cell functions. The method has seen increasing use in fields such as gene therapy, RNA-based vaccines, and genetic engineering. Efficient RNA transfection is essential for manipulating immune cells making them crucial targets for therapeutic interventions. However, transfecting RNA into immune cells, such as T cells, dendritic cells (DCs), and macrophages, presents challenges due to their inherent immune response mechanisms and susceptibility to degradation pathways.

Four widely used RNA transfection techniques – Viral Vector, Lipofection with Lipofectamine, Electroporation, and RNA-loaded lipid nanoparticles (RNA-LNP) – are analyzed here in terms of their efficiency, cytotoxicity, and suitability for different immune cell types. These approaches are commonly applied to introduce RNA into immune cells for gene silencing and other therapeutic applications.

I. What is RNA transfection?

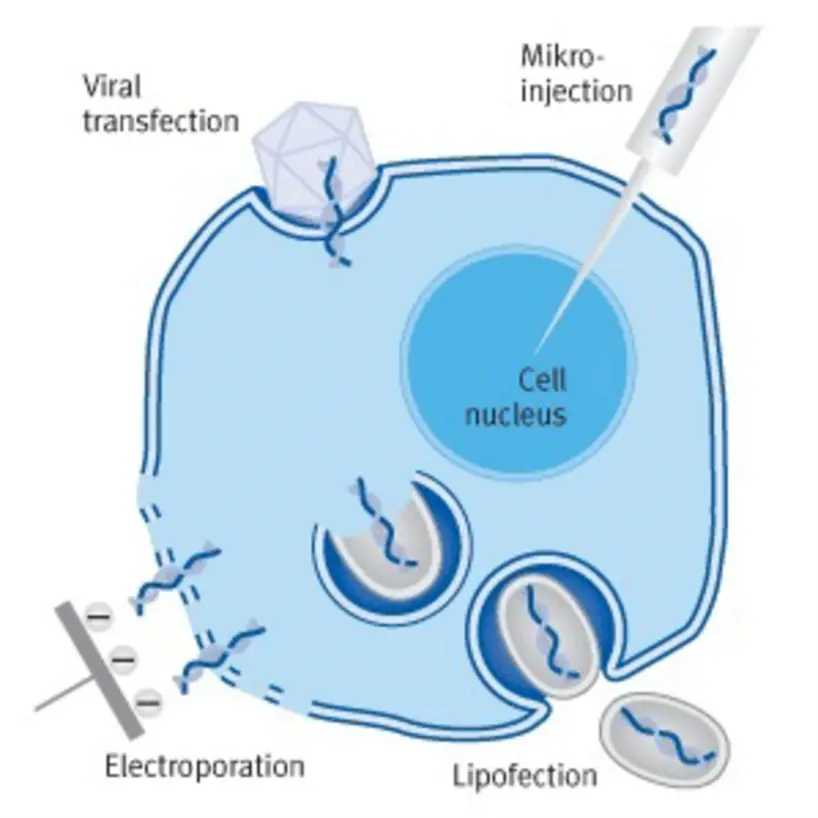

Transfection is the process of introducing foreign nucleic acids (such as DNA, RNA, or small oligonucleotides) into eukaryotic cells. This can be achieved using various chemical, physical, or biological methods. RNA transfection is particularly advantageous over DNA transfection because RNA does not require nuclear membrane traversal and is not integrated into the genome, thereby reducing the risk of insertional mutagenesis and enabling more transient gene expression. However, RNA is inherently less stable than DNA and prone to degradation, especially in immune cells, making the choice of transfection method critical. [1]

There are several techniques for RNA transfection, including viral and non-viral methods. Among the non-viral approaches, lipofection, electroporation, and RNA-LNPs are widely used for their relative ease and applicability to a variety of cell types, such as mamalian cells. While viral methods often offer high efficiency, they are associated with risks such as transgene integration and immune responses. Non-viral methods, on the other hand, offer safety advantages and are being optimized to improve delivery efficiency, especially for difficult-to-transfect immune cells

II. RNA Transfection Methods

A. Viral Transfection or Transduction

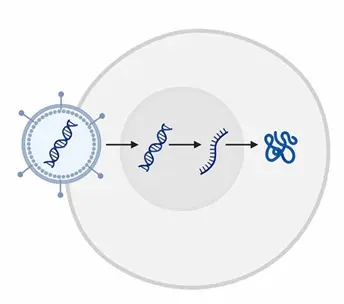

Viral transfection is a gene delivery method that uses viral vectors (e.g., lentivirus, adenovirus, AAV) to introduce nucleic acids into target cells. Viral vectors are engineered to be replication-deficient and safe for laboratory use, while maintaining their natural ability to efficiently enter cells. Viral transfection is widely used for stable or transient expression of genes in both in vitro and in vivo applications.

Mechanism of Viral Transduction : Viral vectors use their surface proteins to bind specific receptors on target cells (tropism), allowing the viral particle to enter via endocytosis or membrane fusion. Once inside, the viral genome is delivered into the cytoplasm (RNA viruses) or nucleus (DNA viruses), enabling transcription and translation of the gene of interest. The inherent efficiency of viral entry and genome delivery makes this method highly effective, even in difficult-to-transfect cell types.

Advantages:

- Efficiency: Viral vectors achieve very high transduction efficiency, including in primary cells and non-dividing cells such as neurons or stem cells.

- Reproducibility: Once produced, viral vectors provide highly consistent gene delivery across experiments.

- Stable expression: Integrating vectors (e.g., lentivirus) allow long-term gene expression, which is essential for many research and therapeutic applications.

- Broad applicability: Viral vectors can be engineered to target specific tissues or cell types (tropism), allowing for in vivo or ex vivo use.

Limitations:

- Complex production: Viral vector generation requires specialized facilities and biosafety measures, increasing experimental complexity and cost.

- Safety concerns: Although engineered to be replication-deficient, viral vectors still carry potential biosafety risks that must be carefully managed.

- Immunogenicity: Some viral vectors can trigger immune responses in vivo, which may limit repeated dosing or affect cell viability.

- Limited cargo size: Certain viral vectors (e.g., AAV) have constraints on the size of the genetic payload they can carry – they are for instance not suited for mRNA transfection.

B. Lipofection (Lipofectamine)

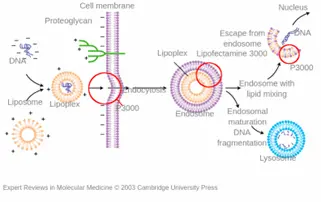

Lipofection is a chemical transfection method that uses cationic lipids to form complexes with RNA molecules, facilitating their entry into cells through endocytosis. Lipofectamine™ is one of the most widely used commercial reagents for this purpose and is known for its high efficiency and reproducibility, particularly in adherent cells and primary cultures. [3]

Mechanism of Lipofection: Cationic lipids – the transfection reagent – interact electrostatically with negatively charged nucleic acids, forming complexes that are then internalized by cells. Once inside, the RNA must escape from endosomes to reach the cytoplasm, which is a critical step for successful transfection. The simplicity of the method makes it suitable for many cell types, including immune cells like macrophages and dendritic cells.

Advantages:

- Efficiency: High transfection efficiency, particularly in easily transfectable cell types such as dendritic cells and macrophages.

- Reproducibility: The process is simple and generally produces reproducible results, making it ideal for large-scale experiments.

- Versatility: Lipofection works well across a wide range of cell types, including primary and hard-to-transfect cells.

- Low toxicity: When optimized, lipofection can minimize cytotoxicity, allowing for good cell viability post-transfection.

Limitations:

- Stability: Lipofection may not be effective in certain cell types, such as T lymphocytes, due to their limited endocytic capacity.

- Residual toxicity: At high concentrations, lipofection reagents can induce cytotoxicity, which may interfere with experimental results.

- Endosomal escape: The efficiency of transfection can be compromised if RNA fails to escape from endosomes, reducing the overall success of the method.

C. Electroporation

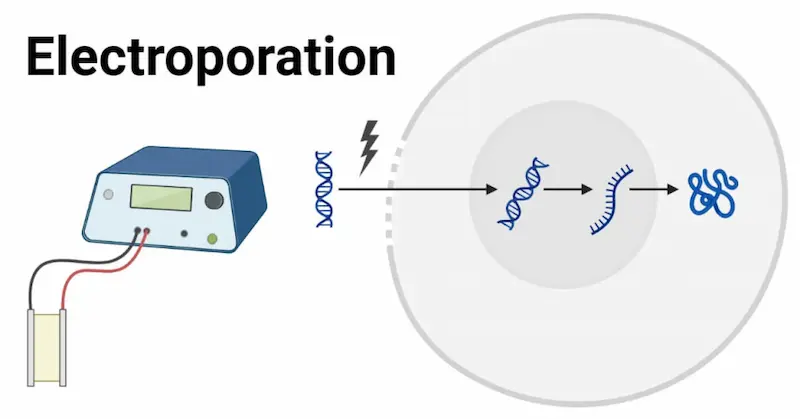

Electoporation is a physical transfection method that uses electrical pulses to create temporary pores in the transfected cell membrane, allowing nucleic acids to enter the cell. This method is particularly useful for transfecting difficult-to-transfect cells such as primary immune cells, stem cells, and certain B cell lines. [2]

Mechanism of Electroporation: During electroporation, an electrical pulse is applied to a suspension of cells and nucleic acids, causing the formation of transient pores in the cell membrane. This disruption allows charged molecules like RNA to enter the cells. Electroporation requires optimization of several parameters, including pulse duration, voltage, and transfected cell concentration, to balance transfection efficiency with cell viability.

Advantages:

- Efficiency for difficult cells: Electroporation is highly effective for cells that are hard to transfect using chemical methods, including primary immune cells and stem cells.

- No vector requirement: Unlike viral and chemical methods, electroporation does not require vectors, which eliminates the risk of integration and immune responses associated with viral delivery.

- High throughput: The method can transfect large numbers of transfected cells simultaneously, making it suitable for high-throughput applications.

- Reproducibility: With proper optimization, electroporation produces reproducible results.

Limitations:

- High toxicity: The application of electrical pulses can lead to significant cell death, especially if the parameters are not carefully optimized.[4]

- Optimization complexity: Each cell type may require specific pulse conditions, making the method less standardized compared to chemical methods like lipofection.

- Specialized equipment: Electroporation requires specialized equipment (electroporators), which can be costly and may limit its accessibility in some laboratories.

- Cost: requires many cells and relatively large amounts of RNA.

- Not scalable in-vivo

For a better understanding to how electroporation compares to RNA-LNP, check our comparative application note: Benchmarking LNP vs Electroporation for eGFP RNA and CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery in HSCs

D. RNA-LNP (Lipid Nanoparticles)

Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) have become a promising alternative for RNA delivery, particularly for RNA-based vaccines and gene therapies. LNPs encapsulate RNA within the nanoparticle core, protecting it from degradation and facilitating its delivery into cells. This method has gained significant attention, especially with the success of mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines.

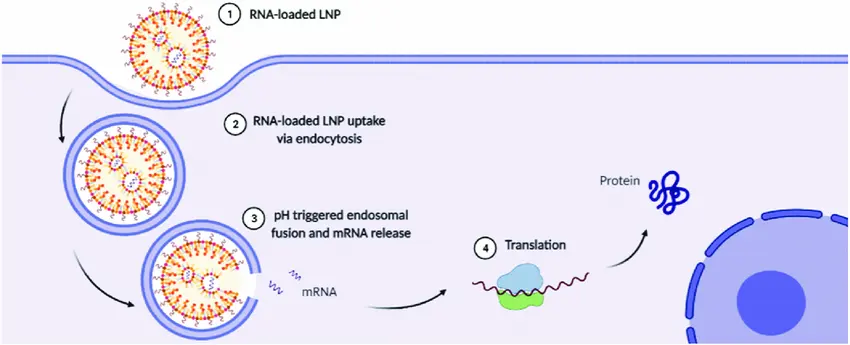

Mechanism of RNA-LNPs: LNPs are formulated from lipids that self-assemble into nanoparticles capable of encapsulating RNA molecules. These RNA-LNP complexes are taken up by cells through endocytosis, after which the RNA is released into the cytoplasm. LNPs can be engineered to improve cell-specific targeting and enhance RNA stability.

Advantages:

- RNA stability: LNPs provide a protective barrier that helps stabilize RNA molecules, preventing their degradation in extracellular environments and within the cell.

- Targeted delivery: LNP formulations can be optimized to target specific cell types, such as immune cells, and to optimize biodistribution, enhancing the precision of gene delivery.

- Lower toxicity: Compared to electroporation, LNPs generally induce less cytotoxicity, resulting in better cell viability post-transfection.

- Versatility: LNPs can be used for a variety of RNA types, including mRNA (messenger RNA), siRNA, saRNA…

Limitations:

- Endosomal release: One of the challenges with RNA-LNPs is ensuring efficient RNA release from endosomes, as failure in this step can limit the overall transfection efficiency.

- Formulation dependence: The efficiency of LNPs is highly dependent on the formulation, which requires optimization for each cell type and experimental purpose.

Summary

| Criteria | Electroporation | Lipofection | RNA-LNP | VIral Vectors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| in-vivo/ex-vivo | ex-vivo | ex-vivo / limited-vivo | in-vivo/ex-vivo | in-vivo/ex-vivo |

| Efficiciency/protein epxression | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| Reproducibility | +++ | ++ | +++* | +++ |

| Cell viability | – | ++ | +++ | – (vector dependant) |

| Ease of use | ++ | +++ | ++ | – (requires biosafety) |

| Versatility | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ (depend on tropism) |

| Cost | – | +++ | ++ | – (high production and QC costs) |

| Cell / tissue targeting | Broad; depends on cell type | Broad, but limited in certain hard-to-transfect cells | Can be engineered for tissue-specific delivery | Dependent on viral serotype or engineered tropism; allows targeted in vivo delivery |

| Stability | Transient | Transient | Transient | Transient |

Legend:

- – = Low

- ++ = Moderate

- +++ = High

III. Applications in Immune Cells

Transfection of RNA into immune cells holds great promise in areas such as immunotherapy and vaccine development. siRNA-based approaches, in particular, are widely used to knock down gene expression in immune cells, enabling the study of gene function and the development of therapeutic strategies.

- Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs): Those stem cells give rise to all blood and immune cells through haematopoiesis, generating both myeloid and lymphoid lineages. As these cells differentiate, they acquire distinct biological properties that can make nucleic-acid delivery challenging. Myeloid cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells develop strong phagocytic and surveillance functions, while lymphocytes like T cells have limited endocytic capacity. These features directly impact transfection efficiency and must be considered when designing RNA-based vaccines or immunotherapies. Though our application note shows that both RNA-LNP & electroporation can be used to transfect them.

- Macrophages and dendritic cells: These cells play a critical role in the innate immune response and are potential targets for RNA-based vaccines and immunotherapies. However, macrophages are often difficult to transfect due to their extensive phagocytic activity and immune surveillance mechanisms.

- Lymphocytes: Lymphocytes, particularly T cells, are challenging to transfect due to their lack of efficient endocytic machinery. Methods like electroporation and LNPs are often more successful for transfecting these cells compared to chemical methods.

IV. Limitations and Future Perspectives

Despite the progress in RNA transfection technologies, several challenges remain. These include the need for more efficient, targeted, and less toxic delivery systems for RNA, especially in immune cells. As RNA therapies move into clinical applications, overcoming barriers such as endosomal escape and RNA degradation remains a priority.

Emerging hybrid systems that combine the benefits of multiple transfection methods (e.g., combining LNPs with electroporation) hold promise in addressing some of these limitations. Additionally, ongoing improvements in RNA-LNP formulations and the development of novel transfection technologies will likely enhance the specificity, efficiency, and safety of RNA delivery in immune cell-based therapies.

Conclusion

RNA transfection in immune cells is a critical tool for advancing gene therapy, immunotherapies, and RNA-based vaccines. While each method – lipofection, electroporation, and RNA-LNPs – has its advantages and drawbacks, careful selection based on cell type, experimental goals, and delivery requirements will ensure the success of transfection experiments. The future of RNA transfection lies in optimizing these methods, potentially through hybrid approaches, to improve their efficiency, reduce toxicity, and enhance targeted delivery, ultimately advancing the field of immunology and therapeutic development.

Looking to get started with RNA-LNP?

Reach out to us to learn how we can help!

References

[1] Mogler & Kamrud, 2015; Oh & Kessler, 2018; Ylosmaki et al., 2019

[2] Jordan et al., 2008; Stroh et al., 2010; Liew et al., 2013; Canoy et al., 2020

[3] Lirong Yi PhD 2025 Improving lipid nanoparticles delivery efficiency of macrophage cells by using immunomodulatory small molecules

[4] Piñero et al., 1997; Kim & Eberwine, 2010; Mali, 2013