Abstract

LNP formation—also known as lipid nanoparticle formation—relies on nanoprecipitation or self-assembly mechanisms that determine the final size, structure, and caracteristics of the particles. Understanding this process is essential for optimizing LNPs used to deliver nucleic acids in vaccines and therapeutics. LNP formation follows four fundamental stages: supersaturation, nucleation, growth, and stabilization. During supersaturation, lipid and aqueous phases mix under controlled conditions, triggering nucleation where initial nanoparticle seeds form. These seeds grow as lipid components assemble around the payload, before stabilization locks in the particle size and morphology. Common techniques, including thin film hydration, solvent injection, impingement jet mixing (IJM), and microfluidics, all exploit these principles which directly influence particle uniformity, encapsulation efficiency, and stability.

Lipid nanoparticle formation mechanisms, also referred to as nanoprecipitation or nanoparticle self-assembly methods, remain relatively not well understood despite their wide usage in nearly all the nanoparticle synthesis methods such as thin film hydration, solvent injection, IJM or microfluidics.

Considering the importance of the physiochemical parameters such as particle size, PDI, encapsulation efficiency, drug loading… of the formed lipid or polymer nanoparticle (such as plga nanoparticles) to their toxicity, drug release, and drug delivery efficiency, having a finer understanding of the chemical phenomenon driving their nucleation, growth, and maturation appears essential for better control of their characteristics.

Lipid nanoparticles (LNP) and organic nanoparticle formation process

Nanoparticles (NP), formation in solution is a complex process that is dependent on the material type and reaction conditions. The classical description of nanoparticle formation has been well established for inorganic nanoparticles, such as gold nanoparticles for example, and it can be generalized to organic NPs including lipid-based nanoparticles . This process is divided into four steps: supersaturation, nucleation, growth, and stabilization or maturation. The relationship between time and the size of the NPs at the different stages of this process is highly dependent on the experimental conditions (physicochemical characteristics of the solute, concentration, charge, diffusivity in the solvent, etc.). Note that other nanoprecipitation technique, such as flash nanoprecipitation, are available, yet they all follow the same principle.

Classical nucleation theory (CNT) for nanoparticle formation

Supersaturation

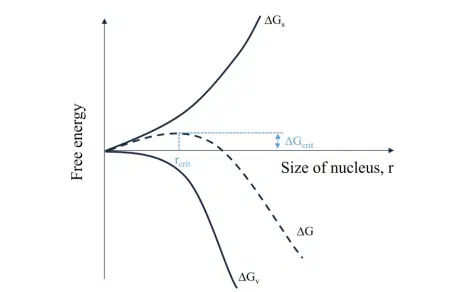

Nanoparticle formation in the solution can be understood as a phase separation process that starts with nucleation, where single units of material (metallic ions, polymer chains, lipid chains…) assemble to form a nucleus. Assuming a homogeneous nucleation, that is when the Nanoparticle synthesis by nanoprecipitation solutes is perfectly dispersed in the medium and nucleation is happening everywhere in the volume and not specifically on boundaries or clusters like it does in water crystallization for example, this phase separation is defined by the system’s free energy:![]()

where ∆Gs is the surface energy, ∆Gv is the bulk energy and γ and ∆gv are the surface tension and the difference in bulk free energy between the two phases respectively.

The nuclei formed become stable and can grow further when they reach a certain critical radius, rcrit, which corresponds to an energy barrier given by the maximum free energy ∆Gcrit.

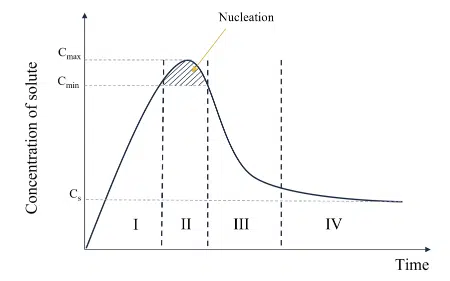

Furthermore, the particle formation process is usually described by a LaMer diagram1 (see on the right) which represents the typical relationship between the lipid or polymer concentration and the time of reaction. The first stage consists of the generation of solutes in the solution. In the case of organic NPs where macromolecules constitute the solutes, this step can be related to in situ polymerization of monomers for example. As we will see hereafter, in most cases of nanoprecipitation of lipid or polymeric nanoparticles, an increase in the concentration of solute is not due to a chemical reaction and a physical increase in the number of solutes but rather due to a change in solubility of the surrounding medium.

Nucleation

The second stage or nucleation, occurs when the concentration of solute is above a critical value, Cmin. The concentration of solute can still increase to another threshold called supersaturation (S), where the maximum concentration is reached, Cmax.

One can define this dimensionless number as :

where χs is the molar fraction of the solute and χsat is the solubility of the solute in the solvent [114].

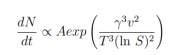

The relationship between S and the nucleation rate of N particles follows an Arrhenius law :

where A is a factor related to the frequency of molecular processes, v is the molar volume and T is the temperature. S is generally considered the driving force for nucleation and tells us that the higher the solubility, the smaller S, the smaller the nucleation rate.

The nucleation rate is also largely influenced by the surface free energy, which represents the energy needed to create a new surface in the solution. This quantity can be changed experimentally using surfactants. The effect of temperature will be discussed further, as it not only impacts the nucleation rate but the diffusion and mixing rates as well.

Looking at organic NPs, the classical nucleation theory (CNT) described above does not strictly apply. First, nucleation does not follow a generation of single molecules and it is more adequate to talk about self-assembly when referring to the generation process of organic NPs. The CNT assumes homogeneous nucleation of spherical nuclei, which is not always the case. Especially in multicomponent systems, made of various polymers, lipids, and/or surfactants, the presence of clusters of solute is very likely. These clusters can serve as more energetically favorable nucleation sites and the bulk energy barrier is reduced compared to homogeneous nucleation.

Moreover, CNT does not take into account the interaction of clusters and/or nuclei with one another. Some non-classical nucleation theories have been explored, taking into account the dynamics of intermediate nanostructures, such as those developed in the review published by Wu et al.

Growth and maturation

When nuclei start to appear and overcome the generation of new solute, the concentration is then decreasing which indicates the growth of the NPs. The classical description of the growth mechanism implies the addition of monomers on the surface of already-formed nuclei. As the diffusion of monomers and nuclei is crucial for this process, it is obviously influenced by the supersaturation, temperature, and pressure in the system. Classical theories do not consider the growth of particles through fusion or aggregation, which limits the practical application of these theories, especially for organic NPs. As of today, a full theoretical description that matches the complex reality of organic NP growth is still lacking, hence we will mainly discuss the findings of this manuscript based on experimental observation.

In practice, nucleation and growth compete and happen simultaneously but ideally, to have a uniform nanoparticle size distribution, these two processes should be temporally and spatially separated. If not, that means that some nanoparticles start growing at the same time as other nuclei are still forming, thus leading to an inhomogeneous particle size distribution.

When the size of the NPs is stable, the concentration of solute finally reaches a plateau, at this stage, the NPs are in equilibrium with their surroundings. The stability of the NPs is a very important issue in drug delivery applications as it requires that the particles undergo post-processing steps prior to their storage and/or transport as well as encounter complex biological fluids. All of this while keeping their physicochemical features intact until they have reached their destination inside the targeted cells or tissues.

Classical nucleation theory applied to LNP formation

In any case, the influence of mixing speed on the process of nanoprecipitation is also not considered in the available models as they mostly consider bulk synthesis by batch process and assume that the time to reach a complete mixing of the initial reagents is negligible compared to the nucleation and growth times.

In a comprehensive theoretical and experimental study Lebouille et al., described the full process of polymer nanoparticle formation via nanoprecipitation using a standard nanoprecipitation method (thin-film hydration). Although a few notable differences are made as compared to CNT, the process is very similar and is illustrated below. For simplicity, the process is described as stages occurring in series with distinct characteristic times but, all steps overlap temporally. After an initial mixing step of the reagents, the nuclei, or first assemblies formed by the nanoprecipitation of the solutes, grow by diffusion-limited coalescence. Nuclei are diffusing in solution and fusing (=coalescing) with one another until the system reaches equilibrium. The NPs stop growing when the surfactant molecules, in excess, have created a protective corona around the polymeric NPs.

Mixing time influence on lipid nanoparticle formation

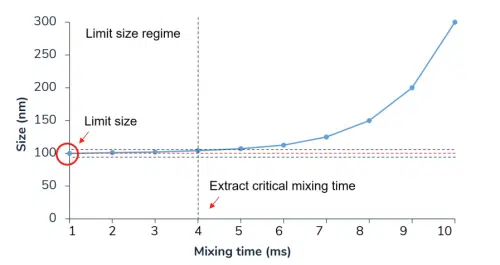

Following this finding, three critical time scales in the polymeric formation process have been identified: the mixing time, tmix, the coalescence time, tcls, and the stabilization time until complete protection of the NPs, tpro.

According to this theory, two different mixing regimes exist: the fast mixing regime where tmix ≪ tcls and the slow mixing regime where tmix > tcls . This is one of the rare research articles describing the fast-mixing regime, also known as the limit size regime, where the NPs size is independent of the mixing time. The intuitive explanation for this regime is that the time scale for mixing becomes much lower than the time scale of the rate-limiting stage in lipid nanoparticle formation, i.e. the growth step, thus allowing the size of NPs to be solely dependent on the chemical composition of the fully mixed phase. To the best of our knowledge, no theoretical research studies exist on the physical principles behind that phenomenon, likely due to the complexity of multi-component systems.

For polymeric nanoparticles, in the slow mixing regime, researchers predict that the particle size becomes independent of the molar mass of the polymer. However, the polymer and surfactant concentrations have a big impact on determining the final NP size: high polymer concentrations will lead to large NPs whereas high surfactant concentrations will reduce the final NP size.

The theoretical description of polymeric nanoparticle precipitation process is a great basis for understanding the LNP formation process via nanoprecipitation as well. Although surfactants are not usually added to lipid formulations, polyethylene glycol (PEG) functionalized lipids serve the purpose of stabilizing agents, and adding more pegylated lipids to a lipid formulation also tends to decrease the final particle size. Recently, researchers tried to elucidate the LNP self-assembly mechanism experimentally in microfluidics. First, Jahn et al. Observed the formation of an intermediate disk-like structure in the nucleation zone of 1,2-dimyristoylsn-glycerol-3-phosphocholine (DMPC) and cholesterol-based LNPs. These results were later confirmed by Maeki et al. in a study where they described the LNPs self-assembly as largely dependent on the organic solvent concentration and dilution rate into the aqueous phase.

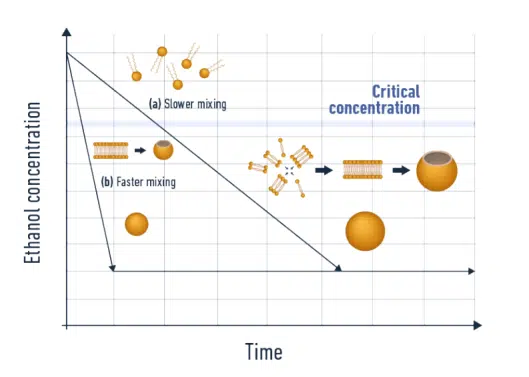

Their system was composed of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphocholine (POPC) dissolved in ethanol as an organic phase and sodium chloride dissolved in water as an aqueous phase. Both phases were later mixed in a microfluidic herringbone mixer at various flow rate conditions. They suggested that the first assemblies created at the aqueous-ethanol interface are disk-like lipid bilayers (in the case of liposomes) which are later fused to form closed LNPs. With lipids being insoluble in water, the dilution of ethanol with an aqueous solution leads to supersaturation and nucleation of the LNPs. Following that is the growth stage, where the disks are diffusing in the solution and fusing with one another. By performing molecular dynamics numerical simulations, the group found that the transformation from disk to spherical LNP was very fast, in the order of ≈ 100 ns, and is therefore not the rate-limiting step in the LNP formation process. The disk formation and their growth by fusion are the rate-limiting steps in LNP formation according to this theory. The researchers found that, aside from the lipid concentration, it is the residence time of the mixing fluids at a critical range of ethanol concentration (between 60 to 80 %) that is most influencing the final size of the LNPs. Hence, according to their findings, the critical parameter here is not the time to reach the maximum mixing efficiency (≈ 90 %) but the time to reach an intermediate mixing efficiency (in the example above, this value ranges from 20 to 40 %).

Furthermore, a higher concentration of lipids leads to an increase in disk-fusion events and ultimately an increase in the final size of LNPs.

Conclusions on Lipid nanoparticle formation

Finally, the main conclusions of these studies on Lipid nanoparticle formation are as follows:

- Mixing time has a major impact on the size of the generated LNP. Faster mixing decreases the resulting nanoparticle size.

- Forming nanoparticles with a high concentration of surfactants or other amphiphilic stabilizing agents decreases their final size.

- Higher concentration of solute leads to the formation of a higher number of nuclei thus an increase in the coalescence events and ultimately an increase in the final size of NPs.

- Viscosity and temperature play a role in determining the final size of NPs, but their influence is harder to predict and measure accurately.

To conclude, considering the importance of the environmental parameters of the particle formation process on the resulting nanoparticle characteristics, a careful selection of the lipids and the use of the appropriate nanoparticle production method is required. For this reason, whether it is for polymer nanoparticle, plga nanoparticle, lipid nanoparticle… batch processes should be avoided, and microfluidics, thanks to its ability to precisely control the environmental synthesis conditions of the nanoparticles, is highly advised for optimal control of the nanoparticles parameters. Additionally, post-processing steps such as nanoparticle purification should be considered to ensure the optimal control of the final nanoparticle characteristics.

Looking to get started with LNP or nanoparticle formulation ?

Reach out to us to learn how we can help!

References

[1] V. K. LaMer and R. H. Dinegar, “Theory, Production and Mechanism of Formation of Monodispersed Hydrosols,” Journal of the American Chemical Society, Vol. 72, No. 11, 1950, pp. 4847-4854. doi:10.1021/ja01167a001